Wrongful Convictions

The following links will take you to sites of people claiming to be wrongfully convicted. We take no responsibility for any information or opinions on these sites.

If there has been an update in any of these cases, or you have a case to add, please contact us.

In Appeals Process

.jpg)

Sadly, Larry lost his battle with cancer while fighting his wrongful conviction in prison. Our prayers are with his family as they overcome this tragedy.

Released

Exonerated

D.A. Dismisses 16-year-old Murder Case on Ethical Grounds

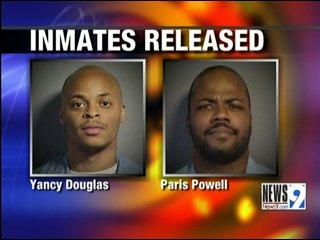

Yancy Douglas and Paris Powell were both cleared of murder

convictions in the 1993 killing of a 14-year-old girl.

The Oklahoma County D.A. said with no other witnesses and no other

evidence, his office had no way to prove the two men were the

gunmen.

The Justice Project

Two More Exonerations Stress the Need for Credible Evidence

October 12, 2009

By John F. Terzano

Two more innocent men have been freed from death row.

Just last week, Yancy Douglas and Paris Powell became the 137th and

138th people to be exonerated from death row. The two men were

convicted of a drive-by shooting in 1993 based on the testimony of

an in-custody informant who had been offered leniency from the

prosecution. The prosecutors at trial withheld information about

this plea-deal from the defense, which resulted in a new trial. All

charges against the two men have now been dropped because of the

unreliability of the in-custody informant’s testimony, the only

evidence that linked Douglas and Powell to the crime.

These exonerations highlight the power prosecutors have in securing

convictions by utilizing in-custody informant testimony, even when

no physical evidence links a defendant to the crime. Testimony by

in-custody informants or “jailhouse snitches” as they are often

referred, is a leading cause of wrongful convictions. With little to

lose, jailhouse snitches have great incentives to provide false

information to prosecutors in exchange for leniency or other forms

of compensation. Deals that are made between prosecutors and

jailhouse snitches do not often come to light when a jury has to

weigh the evidence is a case.

The exonerations of Douglas and Powell

demonstrate, yet again, the very real threat of false testimony and

the strong need for corroborating evidence to ensure that accurate

and credible testimony is presented to juries in criminal trials.

The fairness and accuracy of our justice system is at stake when

jurisdictions do not require mandatory, pre-trial disclosures of all

incentives given to in-custody informant witnesses, as recommended

in

In-custody Informant Testimony: A Policy Review.

Unfortunately, Douglas and Powell are not alone in their experiences

with a prosecution that withheld important evidence. Such acts are

the most common type of prosecutorial misconduct that leads to

wrongful convictions. The flawed trial that led to the wrongful

convictions and death sentences of Douglas and Powell, along with

the cases of the 136 death row exonerees before them, again

highlight the urgent need for reform to address the common causes

that lead to wrongful convictions. As exonerations continue to occur

throughout the country, it is abundantly clear reform is needed to

stem the tide of wrongful convictions and begin to restore

credibility, fairness, and accuracy to our criminal justice system.

According to deathpenaltyinfo.org, 8 Oklahomans

have been exonerated from death row as of August, 2008. DEATH ROW!

Dallas County Texas retested their DNA evidence in early 2008 and found

17 inmates who were wrongfully convicted! 17 inmates doesn't sound like

a large number, but we're not talking about inmates who had spent 30

days in prison or 3 years! Charles Chatman spent 27 years behind bars!

27 years! before DNA evidence cleared him. How many inmates do we have

with no DNA evidence available in their cases? How many wrongfully

convicted people do we have in our prisons? There has to be a better

way! These are lives we're talking about!!! And not just their lives,

but their families' lives as well!

These are stories of PEOPLE who were on death row in OKLAHOMA and were

released. Please read their stories.

Charles Ray Giddens Oklahoma Conviction: 1978, Charges Dismissed: 1981 *

Giddens, an 18-year-old black man, was convicted for the murder of a

grocery store cashier primarily on the testimony of Johnnie Gray, who

claimed he accompanied Giddens to the murder scene. Although Gray was

never indicted, Giddens was sentenced to death after an all white jury

deliberated for only 15 minutes. Giddens conviction and death sentence

reversed by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, which found Gray's

testimony was unreliable and the evidence against Giddens insufficient.

(Giddens v. State, No. F-78-164 (Ct. of Crim. App., 11/17/81)) The

charges against Giddens were dropped.

Clifford Henry Bowen Oklahoma Conviction: 1981, Charges Dismissed: 1986

Bowen was incarcerated in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary under three

death sentences for over five years when the U.S. Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit finally overturned his conviction in 1986. The Court

held that prosecutors in the case failed to disclose information about

another suspect, Lee Crowe, and that had the defense known of the Crowe

materials, the result of the trial would probably have been different.

Crowe resembled Bowen, had greater motive, no alibi, and habitually

carried the same gun and unusual ammunition as the murder weapon. Bowen,

on the other hand, maintained his innocence, provided twelve alibi

witnesses to confirm that he was 300 miles from the crime scene just one

hour prior to the crime, and could not be linked by any physical

evidence to the crime. (Bowen v. Maynard, 799 F.2d 593 (10th Cir. 1986)

and Oklahoma Publishing Co., 7/31/87).

Read "Cowboy Bob..." by Ken Armstrong in The Chicago Tribune

Richard Neal Jones Oklahoma Convicted 1983 Acquitted 1988

Jones was sentenced to death in Oklahoma in 1983. Jones maintains that

he was passed out while his three co-defendants murdered Charles Keene.

On appeal, the Court of Criminal Appeals of Oklahoma remanded the case

for retrial. The Court held the jury was prejudiced by the improper

admission of hearsay testimony and inflammatory photographs. The Court

also agreed with Jones' assertion that the case should be remanded on

the basis of prosecutorial misconduct. Moreover, the Court held, the

case was not one in which Jones' guilt was "overwhelming" and that

Jones' involvement was disputed by the evidence. (Jones v. State, 738

P.2d 525 (Okla. crim. app. 1987) and Oklahoma Publishing Co., 1/18/88).

Gregory R. Wilhoit Oklahoma Conviction: 1987, Acquitted: 1993

Convicted of killing his estranged wife while she slept. His conviction

was overturned and he was released in 1991 when 11 forensic experts

testified that a bite mark found on his dead wife did not belong to him.

The appeals court also found ineffective assistance of counsel. He was

acquitted at a retrial in April, 1993. (Wilhoit v. State, 816 P.2d 545

(Okla. Crim. App. 1991) and The Daily Oklahoman, 4/1/93).

Read "My Nightmare: An Interview with Greg Wilhoit" by Ira Saletan

Robert Lee Miller, Jr. Oklahoma Conviction: 1988, Charges Dismissed:

1998*

Miller was convicted of the rape and murder of two elderly women in

1988. In 1995, Miller's original conviction was overturned and he was

granted a new trial when DNA evidence pointed to another suspect who was

already incarcerated on similar charges. In February, 1997, Oklahoma

County Special Judge Larry Jones dismissed the charges against Miller,

saying that there was not enough evidence to justify his continued

imprisonment. One month later, Oklahoma County District Judge Karl Gray

reinstated the charges in response to an appeal by the District

Attorney's office; however, the prosecution ultimately decided to drop

all charges and Miller was released. (Barry Scheck, et al., Actual

Innocence (Doubleday 2000) and The Daily Oklahoman, 3/1/97).

Read "When the Evidence Lies" by Belinda Luscombe in Time Magazine

Ronald Keith Williamson Oklahoma Conviction: 1988, Charges Dismissed:

1999

Ronald Williamson and Dennis Fritz were charged with the murder and rape

of Deborah Sue Carter, which occurred in Ada, Oklahoma in 1982. They

were arrested four years after the crime. Both were convicted and

Williamson received the death penalty. In 1997, a federal appeals court

overturned Williamson's conviction on the basis of ineffectiveness of

counsel (Williamson v. Ward, 110 F.3d 1508 (10th Cir. 1997) aff'g 904 F.

Supp. 1529 (E. D. OK 1995)). The Court noted that the lawyer had failed

to investigate and present to the jury the fact that another man had

confessed to the crime. The lawyer had been paid a total of $3,200 for

the defense. Recently, DNA tests from the crime scene did not match

either Williamson or Fritz, but did implicate Glen Gore, a former

suspect in the case. All charges against the two defendants were

dismissed on April 15, 1999 and they were released. Williamson suffers

from bipolar depression and has been hospitalized for treatment. (Daily

Oklahoman, 3/18/99 and New York Times 4/16/99).

Read "Life After Death Row" by Sara Rimer in The New York Times Magazine

See Frontline: Burden of Innocence by PBS ---- Williamson is currently

deceased

Curtis Edward McCarty Oklahoma Conviction: 1986, Charges Dismissed: 2007

McCarty, who had been sentenced to die three times and has spent 21

years on death row for a crime he did not commit, has been released

after District Court Judge Twyla Mason Gray ordered that the charges

against him be dismissed. Gray ruled that the case against McCarty was

tainted by the questionable testimony of former police chemist Joyce

Gilchrist, who gave improper expert testimony about semen and hair

evidence during McCarty's trial. Oklahoma County District Attorney David

Prater said his office will not appeal Gray's decision. According to the

New York-based Innocence Project, an organization that assisted McCarty

in his efforts to prove his innocence, during McCarty’s first two

trials, Gilchrist falsely testified that hairs and other biological

evidence showed that McCarty could have been the killer. In both trials,

the juries convicted him and he was sentenced to death. In Gilchrist’s

original notes, hairs from the crime scene did not match McCarty. She

then changed her notes to say the hairs did match him. When the defense

requested retesting, the hairs were lost. A judge has said Gilchrist

either destroyed or willfully lost the hairs. DNA testing in recent

years has also shown that another person raped the victim. McCarty's has

maintained his innocence since his arrest.

(The Oklahoman, May 11, 2007 and The Innocence Project)

Average number of years between being sentenced to death and

exoneration: 9.5 years

Number of cases in which DNA played a substantial factor in establishing

innocence: 17

Released and Waiting for Exoneration

Articles

Article - Prosecutors Target Wrongful Convictions

By Peter Slevin and Kari Lydersen

Washington Post Staff Writers

Monday, April 28, 2008

CHICAGO -- Tabitha Pollock was asleep when her boyfriend killed her 3-year-old daughter. Charged with first-degree murder because prosecutors believed she should have known of the danger, Pollock spent more than six years in prison before the Illinois Supreme Court threw out the conviction.

"Should have known," the high court ruled, was not nearly enough to keep Pollock behind bars.

Five years later, Pollock remains in limbo, freed from prison but not free from the snags of a wrongful conviction that upended her life. With a felony record, she cannot become a teacher, as she wants. She cannot collect damages from the Illinois government. On a trip to Australia, where customs officials questioned her when she arrived, she learned that the murder conviction always follows her.

To fully clear her name, Pollock -- as well as a dozen or so other former Illinois inmates who have been exonerated -- needs an official pardon, which only the governor can give. She applied in 2002 but has received no word.

"I was raised to believe America is a wonderful country, but I have serious doubts about Illinois now," said Pollock, 37. "This whole experience has taught me not to have any hopes or dreams."

A spokesman for Gov. Rod Blagojevich (D) said last month that the governor is flooded with petitions and has not had time to focus on Pollock's case.

Pollock's predicament is becoming more common across the country as more people are exonerated. The New York-based Innocence Project has tallied 215 wrongful convictions in the United States that have been reversed on the basis of DNA evidence.

Many of those former prisoners are seeking redress from the governments that mistakenly jailed them -- but they are kept waiting, whether because of the slow pace of bureaucracy or a lack of procedures or political will to handle their cases.

When the authorities do not certify innocence, "in effect, the sentence just goes on," said Stephen Saloom, policy director of the Innocence Project. Noting that legislators are recognizing "the lingering problems" of the exonerated after their release, he said 22 states and the District provide official compensation in one form or another.

"A recent trend is not only to compensate at a monetary value per year incarcerated, but also to provide immediate services upon release," said Saloom, who said the project's clients spent an average of 11 years in prison. Advocates say the exonerated need help making the transition back into society, especially finding a job.

"It's not enough to let the person out of prison," Saloom said.

Alabama pays exonerated ex-prisoners $50,000 for each year they were incarcerated. New Jersey pays $40,000 or twice the inmate's previous annual income. Louisiana offers $15,000 a year plus counseling, medical care and job training, according to Northwestern University's Center on Wrongful Convictions.

In Illinois, to regain a certifiably clean record and collect compensation -- a lump payment of $60,150 for five years or less in prison, or $120,300 for six to 14 years -- an exonerated inmate must obtain a "pardon based on innocence" from the governor. A 15-member state review board interviews the petitioners and makes a recommendation, but the governor is not obligated to make a decision.

"The governor is not acting on them," said Karen Daniel, senior staff lawyer with the Center on Wrongful Convictions, which is pressing Blagojevich to decide on Pollock's case and others. "In most of these cases, it's really not a hard decision. Sometimes there's still some controversy left after the conviction is thrown out, but in most of these cases there is no disagreement."

Illinois law gives exonerated former prisoners fewer services than paroled convicts. A bill recently passed by the Illinois House and now under consideration by the Senate would change that, while allowing cleared inmates to receive a "certificate of innocence," which would have the same power as a pardon, without going to the governor.

Robert Wilson's experience with the Chicago courts was a case of mistaken identity. He spent nine years behind bars for another man's crime, and it haunts him still.

On Feb. 28, 1997, someone slashed June Siler, 24, with a box cutter as she waited for a bus on Chicago's South Side. The next day, at the same bus stop, police arrested Wilson. Interrogated for nearly 30 hours, he signed a written confession and was charged with attempted murder.

Wilson pleaded not guilty, but Siler pointed him out in court as the man who cut her face and throat. What the jury did not know was that five other victims -- all white, as Siler was -- were attacked and slashed at Chicago bus stops in the two weeks after Wilson's arrest. The slasher was caught and confessed, but police never asked him about the Siler case.

Nine years later, on an appeal filed by the Northwestern team, a court ruled that the jury should have been told about the other cases. Siler came forward and said she had fingered the wrong man.

Wilson, at long last, was free. Yet he left prison with few prospects and deeply in debt because he was assessed child support for his three boys while behind bars. These days, his boys are teenagers and he is "barely making it."

"I feel so bad, I figure I would be better off back in the penitentiary," said Wilson, 52. "Whenever I apply for a job, they see the criminal record and say no. I'm not asking for welfare or a handout; just give me what I deserve."

Marlon Pendleton is also bitter. In 1993, a rape and robbery victim picked him from a police lineup. His attorneys believe that the victim was influenced by seeing Pendleton in handcuffs before she viewed the entire group. Although he repeatedly asked for DNA testing, he was told it would be impossible.

In 2006, a DNA test established his innocence and Pendleton went free. But he has not been pardoned, has not received compensation and has not seen the conviction wiped off his record. Unable to meet the mortgage, his family lost his late mother's home in Gary, Ind. He says his children are suffering.

"I can't get a job," Pendleton said. "Every time I fill out an application, it comes up. What can you do with a prison record and a not very good education? Life has been a living hell."

Daniel, the Northwestern lawyer, said the number of exonerated inmates "probably seems small" in a nation with 2 million people behind bars. "But to me, it's important."

"It's just an enormous wrong we've inflicted on these people, not necessarily intentionally," Daniel said. "His possessions are gone, job is gone, family members are often gone. There's little worse a government can do to a person. We can't in good conscience have a so-called criminal justice system unless we make people whole when we screw up."

One of Daniel's clients is Marcus Lyons, a former Navy Reservist and aspiring computer programmer who spent three years in prison on an erroneous sexual assault conviction.

Lyons was so distraught that after his release in 1991, he tried to nail himself to a cross outside the DuPage County Courthouse.

DDNA evidence cleared him last year. He is still waiting for the Illinois government to make amends.